Sometimes it feels like long after our religious and national holidays have come and gone, Super Bowl Sunday will endure. Along with Black Friday — not Christmas, Black Friday — Super Bowl Sunday is one of the few true American holidays, and maybe the one that best shows us who we are as a people.

Everything about the biggest day of the world’s biggest sport makes the NFL seem invincible. Right down to the Last Days of Rome extravagances the league insists that the host cities provide.

Even the scandals, such as they are — Deflategate and continued rumors of widespread PED use hound both teams in this year’s Super Bowl—are just fuel for football’s fire. Two teams so competitive that they might turn to drugs (that wouldn’t even be illegal outside the context of football) or cheating (in an almost clownish, get-every-edge-you-can mania) just prove that reaching the Super Bowl is worth almost any price.

None of this is an existential crisis. All of it is good if it points fans toward the football field and away from the broken human beings left in football’s wake. All of it is good if it ushers in the next generation of fans — as long as it makes football continue to seem inevitable.

1. Football is to Boxing as Coca-Cola is to Cigarettes

For most of the twentieth century, boxing was arguably the world’s biggest sport. Its athletes were the biggest stars, made the most money, and had the greatest impact on our culture. Boxing played an outsized role in American life. Boxing created celebrities inside the ring and out. The sport was central to important conversations about race, wealth, and patriotism. Major fights were events: before the Super Bowl, boxing matches were the biggest one-offs in sports and pop culture.

In the twenty-first century, boxing is not dead, but it’s far from what it was. It’s hard to be a casual fan of boxing. Boxing talk is not chit-chat. Families don’t gather to watch matches. Matches aren’t network television. Boxing is subscription-only. The fights have lost their hold on our psyche to nearly every other sport, even new upstarts like Ultimate Fighting and mixed martial arts.

Americans simply became less comfortable with the kind of violence boxing represented. Watching Mike Tyson go back and forth between prison and the ring, between being a terror and a joke, was one thing; watching Muhammed Ali deteriorate first inside and then outside the ring was another. Boxing has largely become the cigarette its fans enjoy alone, in the garage. Mainstream America came face to face with boxing’s human costs, and flinched.

Football was, and is, easier than boxing. It’s easier to participate in, whether as a fan or a player; it’s easier to follow every week or every day; and it’s easier on our morality. Its gladiators are hidden behind helmets and pads; its rackets are elevated to the status of official corporations. Like boxing, football elevates individuals into superstars, but unlike boxing, it finds its individuals easier to dispose of. Football generates numbers that allow for a wide variety of second-order fandoms, from gambling to fantasy leagues to obsessive arguments about statistics, awards, and rankings. Football makes for great TV. It gives us the physical displays and contextual heroism we want in sports, but for the most part, keeps its toll at a distance.

Mainstream America came face to face with boxing’s human costs, and flinched.

There’s a cultural analogy here. For most of their lives, my parents smoked cigarettes. (Maybe yours did, too.) My dad started smoking when he was eight years old, and quit in his forties; my mom started in her teens, and thankfully quit just a few years ago, in her sixties. For our entire lives, my parents warned my brothers, sister, and I against taking up smoking. Ultimately, it took a health scare for each of my parents to give up cigarettes altogether.

Smoking was something I never really engaged in, but always tolerated in my parents and my friends who did it. (I tried it myself, but I’ve smoked maybe twenty cigarettes, lifetime, and as many cigars.) It was simply part of the atmosphere of my childhood. It wasn’t until I went away to college and then came back for the holidays that I even realized that my parents’ house smelled like cigarettes. The house I grew up in was saturated with years of tobacco use, and I had never been able to detect it: the smell had always been there, in the same way my parents’ television set was always on.

By the time my parents’ first grandchildren were born, my mom had taken to smoking only outside — not in her own house, not in her children’s houses, and never in front of her children’s kids. None of us had been under any illusions about the health risks of smoking through the 70s, 80s, or 90s, but it took the 00s and 10s to make smoking shameful. Once it happened, it happened fast.

For my part, I have my own vice that I know is bad for me: I like drinking soda — regular Coca-Cola, with the awful corn syrup and everything. Much like cigarettes, I grew up with it, starting with glass bottles of Coke and Pepsi. (In Detroit, we called it “pop.”) I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t allowed — when I wasn’t encouraged — to drink pop.

Today, Coca-Cola is everywhere. (Seriously, try to imagine public spaces where soda isn’t available. There aren’t that many.) It’s bigger than it’s ever been. Along with coffee, soda has largely filled the gap left by cigarettes as a casual, legal stimulant. Big Soda shows no signs of slowing down. But my brother’s kids? They don’t drink pop. Their parents don’t let them. For my niece and nephew, soda is like cigarettes were for us: the thing their parents do that they tolerate, as background. And for them, smoking cigarettes is something they don’t understand at all. It’s just not part of their lives.

Our parents’ (and their parents’) generation had boxing and cigarettes; ours has football and Coca-Cola. Whether the one will or won’t follow the decline of the other is an open question.

2. Football as a mandatory experience

I played organized football in junior high and high school; before that, I played unorganized football for as long as I can remember. My two brothers also played high school football, and my sister was the best/most-feared athlete in our neighborhood. My cousins and my best friends all played. We had a lot of unsupervised time as children, and spent most of it either playing sports or finding some other way to risk life and limb.

The closest thing I’ve seen to my childhood experience of football — chaotic, violent, unbelievably fun — are these clips from The Flaming Lips documentary The Fearless Freaks:

(Let's see if the video embed still works! Probably not in email, sorry, folks.)

That experience changed when official, school-sanctioned football became available to us. Football was now mandatory. My parents, aunts, uncles, teachers, you name it, saw no reason why a large boy with good athleticism and a head on his shoulders could not, would not, or should not play football.

My dad hadn’t been able to play high school sports because he had a job; he insisted that his children have that experience. My older brother was told before his freshman year he’d be cut out of that year’s Christmas gifts if he didn’t play, and I still don’t know whether it was a joke.

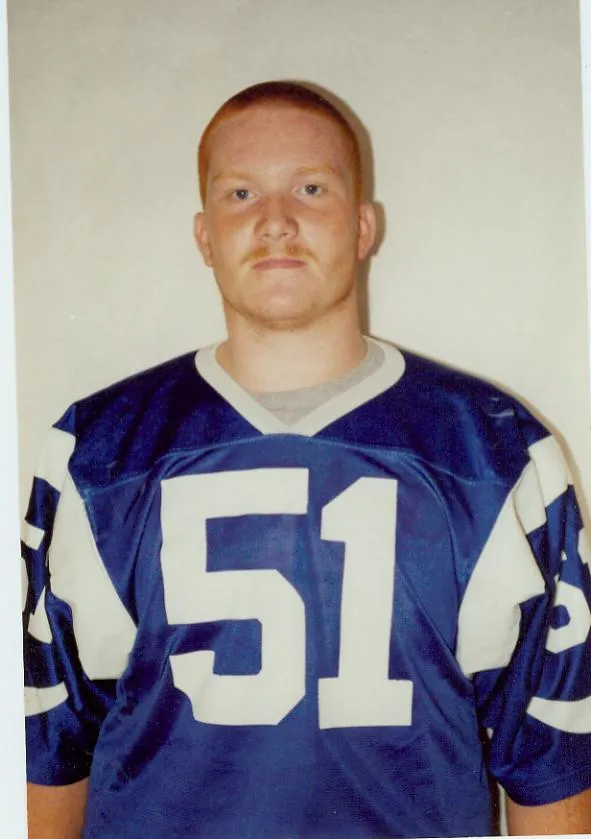

I was pretty good, at least by the standards of our not-very-good teams. I played varsity and started at defensive line as a tubby, 14-year-old sophomore. This meant I got to play on the same team as my brother, a senior—I’m still grateful that I got to do that. I wasn’t tall or fast enough to be considered for Division I, scholarship-level football, but got recruited by some liberal arts colleges and Ivy League schools. I was the jock valedictorian, proudly wearing my varsity jacket to my AP Calc classes.

But I paid the price, too: surgery on both knees my freshman year, a gash across my hand my senior year that took three stitches to close (which I stupidly covered with a filthy glove so that I could continue to play), broken fingers and sprained ankles, more dings and bruises than I could count. I also missed opportunities — training for football every summer precluded any kind of academic camp or extracurricular nerdy business I might have gotten up to. When I was applying to colleges, I knew out-of-state schools by their sports reputations and little else: Northwestern was in the Big Ten, so it was on my radar; the University of Chicago (where I eventually spent a year in graduate school) was not.

I was lucky, though, that at least to my knowledge, I got through my football years without having a concussion, or traumatic brain injury (TBI). That happened years later.

3. What a traumatic brain injury is like

In 2009, I survived a thirteen-story fall from a hotel room window. I broke my right arm and leg, sustained a deep bruise that turned into an abscess on my right flank, took a long cut across my forehead. My least serious injury at the time was what was thought to be a mild concussion. I was lucky to be alive.

The immediate symptoms of the concussion were few: loss of memory, including of the event; some hallucinations, waking dreams that were compounded by my pain medication; and irregular sleep patterns. But about a year later, I had my first seizure. Later, I began to lose memories. I had wild mood swings and migraine headaches that kept me in bed for whole days. I found it hard to concentrate, harder to stay awake. Some days I would feel perfectly fine; on others, I felt like HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

My mind is going. I can feel it. I can feel it. My mind is going.

There is no question about it. I can feel it. I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m a… fraid.

It took some time to pinpoint the cause of these symptoms. Some doctors thought it was a bad medication interaction; others wondered if it was the onset of multiple sclerosis. A week spent hooked to a video EEG machine showed an electrical flutter: a tiny bit of brain damage, the legacy of what was thought to be the mild brain injury from two years before.

To my knowledge, I only suffered a single brain injury in my life. I don’t have chronic traumatic encephaly, which is a result of continued injuries, often before an earlier injury has had time to heal. But when I read about football players like Mike Webster, the Pittsburgh Steelers center whose autopsy began the current NFL concussion controversy, or Dave Duerson, the brilliant Bears safety who decried attempts to rein in head-to-head hits but later committed suicide with instructions to examine his body for signs of damage, it feels too familiar. I know something of what it means to love the game that much, and I know something of what it means to suffer these symptoms.

I know something of what it means to feel like one way or another, voluntarily or involuntarily, you must become something you are not.

I still watch and enjoy football — even though, like smoking cigarettes or drinking Coca-Cola, I’m pretty convinced it’s not good for me.

The biggest difference is that the part of football I used to love best — the contact, the acrobatic violence, the hits — is the part I now enjoy least. And on-field injuries, especially injuries to the head, bring on something very close to symptoms of PTSD.

My brother coaches high school football now, and we usually watch pro and college games together. We focus on Xs and Os, strategy and playmaking. Football is probably the most intellectual game from a coaching standpoint — the most complicated, the most experimental, the most scientific. It’s beautiful in the same cerebral way macroeconomics or asteroid collisions are beautiful. And it’s still viscerally thrilling to watch giant men in peak physical condition contort their bodies in ways I only wish I still could. In these moments, I can forget everything I know.

I still watch football; I still drink Coca-Cola. (2025 update: I drink Coke Zero now.) I do these things in bad faith. I do them because they are ubiquitous; I do them because I do not know what I would do, if I did not. I do not know who I would be.

But any of these things could change tomorrow — and I have to confess, I don’t know how I would feel if they did. Cheated? Grateful?

Nothing is inevitable. Not even the NFL. Today it is a perfect machine of violence, spectacle, intrigue, and entertainment; today it is boxing, cigarettes, and Coca-Cola combined. Tomorrow it could be reduced to a fraction of itself, something at the periphery, a familiar scent in the air. Will our children even remember what it was like?

You just read issue #177 of Backlight. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.